Reframing Todd Haynes: Feminism’s Indelible Mark by Theresa L. Geller and Julia Leyda

In memory of Leo Bersani (1931–2022)

CAROL (2015) SOLVES A historiographic problem: that of representing a happy lesbian (or two) around midcentury. Written by Phyllis Nagy and directed by Todd Haynes, the film takes its source material from Patricia Highsmith’s The Price of Salt (1952), a novel that itself overcame something of an identity crisis. Highsmith initially released the romance under the pseudonym Claire Morgan to excuse herself from the pathology of the “lesbian-book writer.” By the time Highsmith’s name was printed on the cover, the book had been retitled Carol. It’s as if the novel found itself unable to resist Carol Aird’s magnetic pull, ready to surrender to the urge to be near her, to be her.

In Highsmith’s story, that urge is Therese Belivet’s; Rooney Mara and Cate Blanchett portray Therese and Carol on the screen. The characters first encounter each other at the department store where a young, single Therese works and an older, married Carol shops. After Therese sends Carol a Christmas card (in Highsmith’s novel) or returns the gloves that Carol left, perhaps deliberately, on a counter (in Haynes’s film), the two begin a passionate affair. A tumultuous road trip and an acrimonious divorce incite Carol to “release” Therese. Yet the lovers ultimately reunite, choosing each other and a life together. They get a happy ending.

Therese and Carol are no contemporary heroines; sex is for them not an object of pride or militancy. Carol positions neither Highsmith’s story nor its characters as “ahead of their time,” the very expression implying a historical narrative opposing a straight past to a queer present. Mara’s Therese and Blanchett’s Carol are of the early 1950s, and so is the film’s visual style.

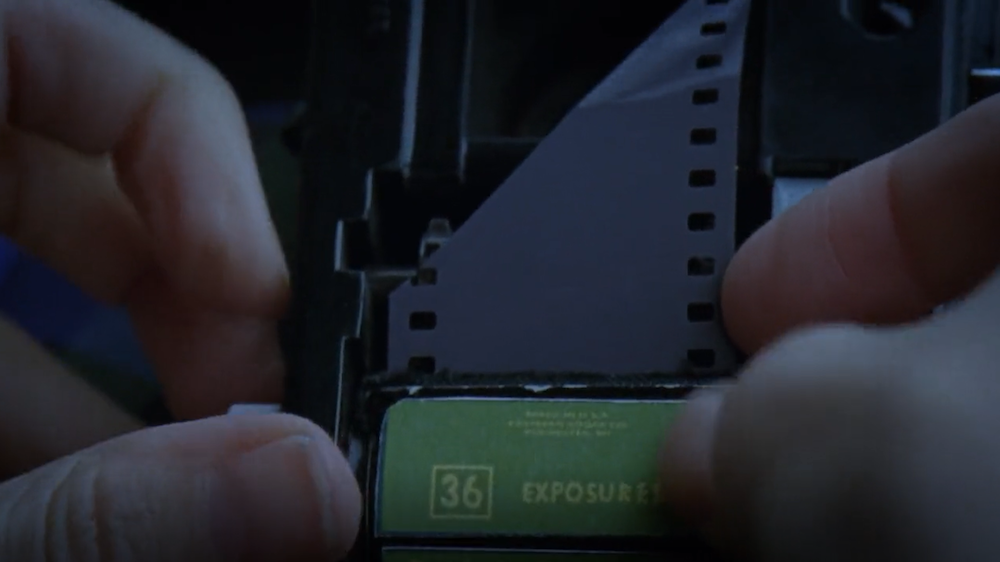

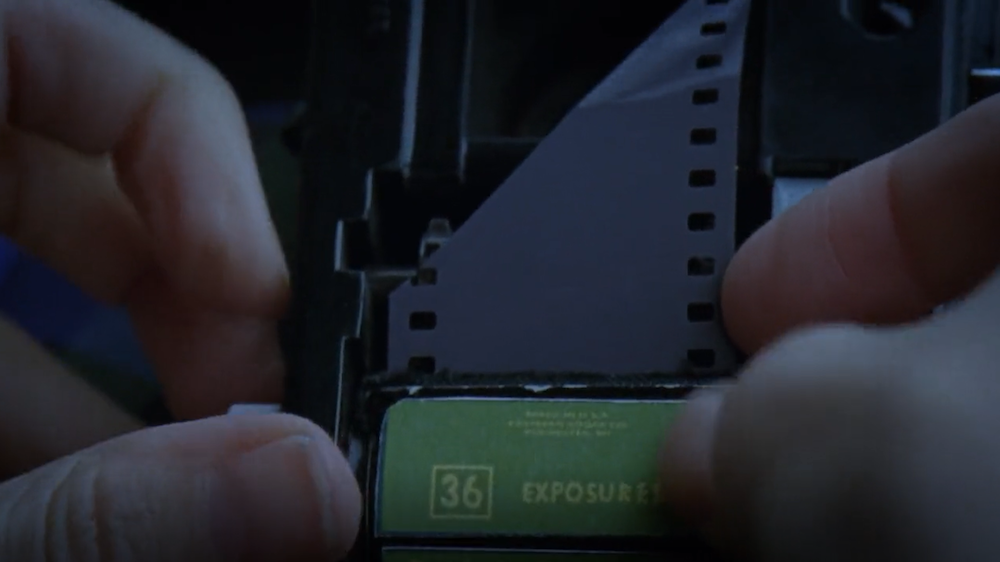

Photography most noticeably anchors Carol in the mid-20th century. In Nagy’s screenplay, Therese turns a photography hobby into a full-time occupation — a departure from Highsmith’s novel, in which the character aspires to work as a set designer for the theater. The shift in career is significant. Scenes of picture-taking and photographic processing confirm Carol’s status as a meditation on appearance and perception, tallying the pleasures and dangers of seeing and being seen. We watch Therese watch Carol with fascination. We watch Carol receive the gaze and return it; early in the film, she gifts Therese a camera, establishing herself as both model and patron. Practices of urban photography like Therese’s inform the film’s visual identity. Edward Lachman’s textured, prismatic cinematography, in which the action is refracted through scratched mirrors and windows covered in rain droplets, takes inspiration from the work of postwar women photographers, such as Vivian Maier, Ruth Orkin, Helen Levitt, and Esther Bubley.

Carol’s adherence to a midcentury style of visual representation is salient, given that a story like this one couldn’t, of course, have been filmed at the time. Until 1968, Hollywood studios observed the Motion Picture Production Code, commonly called the Hays Code, which prohibited nudity and “lecherous or licentious notice thereof” and “sex perversion or any inference to it.” By the 1960s, an informal liberalization of the Code would permit the representation of lesbian desire in, for instance, the belated film adaptation of Lillian Hellman’s 1934 play, The Children’s Hour. But that representation was conditional: lesbian desire had to be tragic, paid for through the loss of a life. In Carol, too, lesbian desire comes at a cost. Aird gives up custody of her daughter in exchange for occasional, likely supervised, visits. Still, Carol isn’t forced to pick either queer repression or fatal consummation. She can embrace lesbian love and a full life, and she does.

Whereas the cinematic representation of lesbian happiness proved impossible in the early 1950s, lesbian happiness itself, Haynes insists, didn’t. How does Haynes affirm the possibility of lesbian love and life at midcentury while maintaining fidelity to the aesthetics of an era that prohibited their representation? Part of the answer to this question lies in the medial displacement operated by Haynes and Lachman — the importation of an aesthetic of still photography into the domain of the moving image. With Carol, Haynes pastiches not ’50s cinema, as he does in Far from Heaven (2002), but ’50s photography. In its proximity to anthropology and sociology, the photographic style grants the alibi of documentation. Carol pushes cinema toward a journalistic art form that entails its own set of expectations regarding the representation of sexual difference. This representation, while subject to censorship, was never regulated by the Hays Code.

That in Carol photography saves cinema from homophobia is a simplistic observation, and a partial one. The happy ending is made possible not by cinema’s attunement to photography, but by the failure of both modes of representation. The ending depicts Therese and Carol’s first and second encounters after months of silence. At a restaurant, a nervous Carol invites Therese to move into her new apartment. Carol anticipates a rejection, and a rejection she receives. With nothing to lose, she professes her love. The declaration is neither reciprocated nor unreciprocated: a male friend hails Therese, thus interrupting the conversation. Therese heads to a party with the man in question, and Carol honors a dinner reservation with a group of friends. Soon, Therese leaves the party to return to Carol. The camera pans across the dining room, scanning for a familiar face. Having located Carol, Therese stands immobile for a few seconds before proceeding in her past-and-future lover’s direction. Slow motion prolongs each step. As Therese walks toward Carol, the frame jitters. Their eyes meet, and their mouths — Therese’s first, Carol’s second — curve into smiles, faint but exuberant. We cut to black.

The jittery frame constitutes an anomaly in a film where the camerawork otherwise emulates the titular character’s effortless grace. In the ultimate scene, the mode of representation that Haynes and Lachman have crafted out of cinema and photography appears too weak to bear the happy ending toward which Therese and Carol are headed. The frame trembles until it implodes, with a cut to black. Midcentury lesbian happiness can reside in cinematic form, after all. Or, more accurately, it can reside in a certain process of deformation: Therese and Carol gain access to a full life that is also a queer life through the dissolution of a mode of representation. If, for Leo Bersani, the formal glitches of Freud’s theory of sexuality dispense some truth about the incoherence of desire and relation, the dissolution of form in Carol predicates queer futurity on escaping a regime of compulsory visibility and legibility.

Patricia White describes Carol as a reverie in her contribution to Reframing Todd Haynes: Feminism’s Indelible Mark, a new volume co-edited by Theresa L. Geller and Julia Leyda. A portion of Carol’s ending, stretching from Therese and Carol’s truncated reunion to Therese’s car ride to the party, reprises, from new vantage points, the film’s opening sequence. White receives the flashback that makes up the bulk of the film as lesbian wish fulfillment, a fort-da game wherein Therese gets to relive having Carol and losing her, knowing that she can now have her again. In White’s interpretation of Carol, too, a formal intervention — the framing device of the reverie — configures the relation between gender, sexuality, behavior, and identity.

The interplay between the formal and the social in Haynes’s filmography also piques Lynne Joyrich’s curiosity. Her essay for Reframing Todd Haynes submits that the filmmaker’s work “addresses cinematic and social issues, yoking the two together (and revealing how mediatized and social formations are always so yoked).” Joyrich has long formulated queerness in medium-specific terms; her 2001 essay “Epistemology of the Console” offered a televisual spin on a classic of queer theory, Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick’s Epistemology of the Closet (1990). For Joyrich, what sets Haynes apart is his commitment to problematizing both the intimacies and frictions between identity, on the one hand, and medium and form, on the other. The feminist and queer politics of Far from Heaven, Haynes’s homage to the melodramatist Douglas Sirk, emerge from the enmeshment of media history with the history of social and identity struggles. Far from Heaven, Joyrich summarizes, “thinks through its social questions by way of the media and mass cultural ones, revealing in the process how the two are always intertwined and how feminist and queer interventions thus necessitate media interventions, and vice versa.”

Reframing Todd Haynes sets out to assess the influence of feminism, primarily, on Haynes’s oeuvre. Wide-ranging in its themes, methods, and insights, Geller and Leyda’s collection dispels all doubts that a single-director focus might restrict scholarly ambition. Reframing Todd Haynes occupies a register of inquiry seldom rewarded by a contemporary academia that values garish polemics: a sustained, nearly obsessive, attention to individual films. The contributors’ patient interpretations make clear that the most meticulous methods for deriving meaning from art often are the most pleasurable to encounter.

Geller traces Haynes’s artistic and intellectual trajectories in a thoroughly researched introduction that draws abundantly on the filmmaker’s eloquent observations about art, theory, and identity. After the 43-minute Superstar: The Karen Carpenter Story (1987), featuring a cast of Barbie dolls, garnered copious praise from cinephiles but was prevented from circulating widely by copyright restrictions, Haynes made Poison (1991), his splashy debut feature. Caught in the controversies surrounding the National Endowment for the Arts in the late 1980s and early 1990s, the anthology film, a tribute to Jean Genet by way of Rainer Werner Fassbinder, has typically been associated with the loose movement that B. Ruby Rich has called New Queer Cinema (NQC). Geller reports that Haynes has struggled with the possibly reductive NQC affiliation, but has had “no qualms about being branded a director of women’s films.” Besides Far from Heaven and Carol, Safe (1995) and the HBO miniseries Mildred Pierce (2011) both concentrate on women’s status and experience. Fassbinder once observed that in Sirk’s films “women think,” and the same could be said of Haynes’s female characters.

Haynes truly earns his badge as a director of women’s films, in Geller’s estimation, through his continued engagement with feminist theories of form. Haynes is a scholar’s filmmaker if there ever was one. Undeniable is the impact of such film theorists as Laura Mulvey, Biddy Martin, Linda Williams, and Mary Ann Doane on his creative process. The privileged role that both female characters and feminist theorists occupy in Haynes’s filmography prompts Geller to inscribe it in a genealogy of “new feminist cinema,” where the filmmaker stands alongside figures like Chantal Akerman, who died in 2015 and to whom Reframing Todd Haynes is dedicated.

Some chapters in Reframing Todd Haynes carry the mission of situating Haynes’s work within a broader cartography of feminist cinema. Geller’s own mark on the volume’s first third proves indelible. In addition to composing the introduction, she co-authored one chapter and solo-authored another. The latter constitutes an impassioned rejoinder to Murray Pomerance’s critique of Haynes’s purportedly naïve gender and class politics in Safe. Pomerance, holds Geller, “would rather accuse Haynes of ignorant complicity than take the film’s ‘masculine-phobic’ critique of heteropatriarchy at face value.” Geller aligns Haynes’s stance on middle-class female domesticity in Safe with Akerman’s in Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975). Both films inhabit “sensitivity” as a site of feminist critique, magnifying the way “the slightest shift in pressure threatens to expose the extensive repressions and oppressions (desire, anger) required to maintain women’s compliance in heteropatriarchal capitalism.”

Bridget Kies, Mary R. Desjardins, and Rebecca M. Gordon all contribute predominantly feminist interpretations of Haynes’s films. Gordon, for example, addresses the filmmaker’s collaboration with actor Julianne Moore in Safe and Far from Heaven. (Moore also appeared in Haynes’s Wonderstruck [2017] and is set to star opposite Natalie Portman in his upcoming May December, currently in pre-production.) The chapter zooms in on the physical transformation undergone by Moore for both shoots. Moore was pregnant when she played Cathy Whitaker, a character who was not, in Far from Heaven. Efforts to conceal the star’s pregnancy, writes Gordon, “communicate unanticipated meaning.” In their uncanniness, Moore’s readjustments and realignments, somehow at once too sudden and too studied, mirror the film’s defamiliarization of the familiar as a pastiche of 1950s melodramas that were themselves, for the most part, adaptations and remakes.

Yet the ranking of Haynes’s credentials — as a maker of women’s films first, queer films second — proves wobblier than initially suggested. Many contributors turn their attention to the traffic between feminist and queer, terms that point to different, and, in each case, inconsistent, narratives of personal and collective identities, systematic critique, and social progress. At its best, Reframing Todd Haynes shows that the filmmaker’s corpus prevents us from defining one term without appealing to the other. In a superb chapter on, among other things, Haynes’s short Dottie Gets Spanked (1993), Noah A. Tsika picks as an epigraph one of the axioms inventoried in the introduction to Sedgwick’s Epistemology of the Closet: “The study of sexuality is not coextensive with the study of gender; correspondingly, antihomophobic inquiry is not coextensive with feminist inquiry. But we can’t know in advance how they will be different.” As he proceeds to “queer female stardom from MGM to Todd Haynes,” Tsika models an approach to Haynes’s work that doesn’t presume the stability of feminism’s meaning, queerness’s meaning, and the meaning that their collision produces.

The collection loses steam, if only slightly, when it labors to justify the privileging of feminism in both its subtitle and its introduction. Haynes’s track record as a good student of feminist theory can’t seem to dispel a certain discomfort around the decision to devote some 15 feminist essays to the work of a gay man. One strategy for managing this discomfort is to appeal, as do Geller (in the introduction) and Leyda (in a chapter), to a framework like Robyn Wiegman’s “queer feminist criticism.” This framework recognizes the interwoven political and theoretical genealogies that have shaped the rubrics of queerness and feminism.

Another strategy consists in registering the direct impact of women, and one lesbian in particular, on Haynes’s filmmaking, indeed on his very ability to make films. One chapter, by Geller and David E. Maynard, retraces producer Christine Vachon’s “filmic signature.” Vachon represents Haynes’s most important and consistent collaborator. A glance at her filmography — which includes such cult and critical favorites as Larry Clark’s Kids (1995), John Cameron Mitchell’s Hedwig and the Angry Inch (2001), Paul Schrader’s First Reformed (2017), and Janicza Bravo’s Zola (2020) — would suffice to convince anyone of her outsized impact on independent US cinema more broadly.

Acknowledging Vachon’s work and influence is essential, but in the context of Reframing Todd Haynes, the gesture has unintended effects. Anxieties concerning a clash between the volume’s politics and its subject’s identification are tethered to the current moment of identity politics. In the sexual taxonomies of the 21st century, categories that equate behavior and identity appear detached from histories that in fact, as Wiegman reminds us, overlap. Turning to Vachon for a solution to the problem of supposedly incommensurable politics and positions ratifies a contemporary configuration of identity politics that may not best serve feminist and queer interests. The gesture offloads onto someone else, a lesbian, the burden of staging a performance of the self that matches certain visions of feminism, queerness, and queer feminism.

If form is as important to Haynes as the volume’s editors and contributors assert — and it is — then we must take seriously the ways formal experimentation enables both the filmmaker and his audience to think of identity anew. In Haynes’s company, we may detach from the belief that identity categories constitute stable and transparent social facts that art merely reflects. In Carol, the deformation of a photographic style makes possible a midcentury lesbianism defined by its very invisibility and illegibility. Carol and Therese’s life together can begin only once they escape the film’s regime of representation.

An interest in illegibility also animates Haynes’s unconventional flirt with the biopic. Velvet Goldmine (1998) and I’m Not There (2007) allegorize the lives of musical icons who have embodied different archetypes of masculinity: the glam rockers David Bowie, Bryan Ferry, and Marc Bolan in one case, the singer-songwriter Bob Dylan in the other. Haynes plays with the notion of alter ego to distill something of these figures’ essence while estranging us from them. Haynes’s displacement of iconicity, Lee Edelman has held, exposes identification as self-differentiation — the management of an absence within the self. I’m not there.

Haynes’s deviation from contemporary identity politics, paired with his predilection for period dramas, might suggest a romanticization of the past. His films, however, don’t return to some mythical “back then” when sexuality had yet to reticulate into the identity categories that now define us. The mediation of history grants opportunities for formal experimentation, and it is form, we have seen, that at least provisionally suspends the codes whereby identity is governed. Haynes has exhibited a fondness for the melodrama, a mode that, as he has noted and Jonathan Goldberg has paraphrased, risks inscribing “real women in a position of submission identical to their placement in the systems of domination feminism opposes.” In a number of Haynes’s films, characters find themselves crushed by the pressures of the identities they are ascribed and the positions they are made to occupy. At the same time, form, specifically what Haynes has called “homoaesthetics,”[1] cultivates a difference within the self to alleviate some of those pressures.

Haynes’s sharpest articulation of homoaesthetics may be Far from Heaven. It has often been said that the film makes explicit what in Sirk’s melodramas had to remain implicit. By this measure, the interracial friendship in Imitation of Life (1959) becomes, in Far from Heaven, an interracial romance between Moore’s Cathy and Dennis Haysbert’s Raymond Deagan. Likewise, the covert homosexuality of Rock Hudson, Jane Wyman’s co-star in All That Heaven Allows (1955), gives way in Far from Heaven to a character, Cathy’s husband Frank Whitaker (Dennis Quaid), who comes to terms with his own attraction to men.

But Haynes’s “appearing act,” if you will, is far from heroic. It casts doubt on the assumption that making the subtext text should clarify a film’s politics. After all, the interracial friendship between Annie Johnson (Juanita Moore) and Lora Meredith (Lana Turner) in Sirk’s Imitation of Life — or between Delilah Johnson (Louise Beavers) and Bea Pullman (Claudette Colbert) in John M. Stahl’s 1934 version — isn’t devoid of such romantic signifiers as faithfulness and shared domesticity. Far from Heaven’s homosexuality riffs on Imitation of Life’s homosociality, with new characters and settings. The inclusion of a gay male character in Far from Heaven, rather than signaling a self-congratulatory embrace of a liberal politics of visibility, brings into sharp relief queerness’s irreducibility to any one individual. Nothing in Far from Heaven is less queer than its prominent homosexual character.

Far from Heaven’s queerness lies, most of all, in its formal interventions. These activate processes of identification through which identity comes to appear different from itself — an imitation of life. The character best positioned to welcome queer identification in Far from Heaven is, improbably, not the legibly queer one, but the one whose life is troubled by queerness. The resentful and violent Frank invites little identification, which Quaid’s one-note portrayal only exacerbates. Spectators are encouraged instead to inhabit Cathy’s subjectivity, to see the world through her eyes. Cathy isn’t a queer character, but much like the glam rockers who inspired Haynes for Velvet Goldmine, a queer icon. She gasps, aches, regrets, and looks fabulous doing it all. Cathy longs to be free, similar to the scarf that a gust of wind sends flying off before Raymond recovers it. Sandy Powell’s impeccable costume design, in shades of violet, emerald, and rust, exemplifies what Sirk has described as the indistinction between “a dead thing and a live thing.” Moore’s performance is heightened and offbeat. She accumulates emotional “fakeouts,” looking as though she were about to miss the emotional mark, only for us to realize that we had the wrong mark in mind.

Queerness also lies in Far from Heaven’s own identification with Sirkian melodramas. Reframing Todd Haynes employs Elizabeth Freeman’s concept of “temporal drag” to designate, as Geller puts it, Haynes’s ability to convert “the pull of the past on the present in[to] affective and affecting scenarios.” With its parade of stylish outfits — no, looks — Far from Heaven underlines the drag in temporal drag. The film itself approximates a lip-sync performance to the tune of Sirk’s midcentury melodramas. The lip sync, here and elsewhere, induces difference in sameness. Rather than correcting the politics of the source material, it repeats them with a wink.

Perhaps best summed up by lip syncing, the “Haynes code” does not improve identity or history; it pastiches them and, in doing so, makes them inconsistent, unrecognizable, such that those who bear their weight might experience temporary relief.

Jean-Thomas Tremblay is the author of the forthcoming Breathing Aesthetics and a co-editor of Avant-Gardes in Crisis: Art and Politics in the Long 1970s.

[1] In the out-of-print “Homoaesthetics and Querelle,” subjects/objects 3 (1985): 71–99.

¤

CAROL (2015) SOLVES A historiographic problem: that of representing a happy lesbian (or two) around midcentury. Written by Phyllis Nagy and directed by Todd Haynes, the film takes its source material from Patricia Highsmith’s The Price of Salt (1952), a novel that itself overcame something of an identity crisis. Highsmith initially released the romance under the pseudonym Claire Morgan to excuse herself from the pathology of the “lesbian-book writer.” By the time Highsmith’s name was printed on the cover, the book had been retitled Carol. It’s as if the novel found itself unable to resist Carol Aird’s magnetic pull, ready to surrender to the urge to be near her, to be her.

In Highsmith’s story, that urge is Therese Belivet’s; Rooney Mara and Cate Blanchett portray Therese and Carol on the screen. The characters first encounter each other at the department store where a young, single Therese works and an older, married Carol shops. After Therese sends Carol a Christmas card (in Highsmith’s novel) or returns the gloves that Carol left, perhaps deliberately, on a counter (in Haynes’s film), the two begin a passionate affair. A tumultuous road trip and an acrimonious divorce incite Carol to “release” Therese. Yet the lovers ultimately reunite, choosing each other and a life together. They get a happy ending.

Therese and Carol are no contemporary heroines; sex is for them not an object of pride or militancy. Carol positions neither Highsmith’s story nor its characters as “ahead of their time,” the very expression implying a historical narrative opposing a straight past to a queer present. Mara’s Therese and Blanchett’s Carol are of the early 1950s, and so is the film’s visual style.

Photography most noticeably anchors Carol in the mid-20th century. In Nagy’s screenplay, Therese turns a photography hobby into a full-time occupation — a departure from Highsmith’s novel, in which the character aspires to work as a set designer for the theater. The shift in career is significant. Scenes of picture-taking and photographic processing confirm Carol’s status as a meditation on appearance and perception, tallying the pleasures and dangers of seeing and being seen. We watch Therese watch Carol with fascination. We watch Carol receive the gaze and return it; early in the film, she gifts Therese a camera, establishing herself as both model and patron. Practices of urban photography like Therese’s inform the film’s visual identity. Edward Lachman’s textured, prismatic cinematography, in which the action is refracted through scratched mirrors and windows covered in rain droplets, takes inspiration from the work of postwar women photographers, such as Vivian Maier, Ruth Orkin, Helen Levitt, and Esther Bubley.

Carol’s adherence to a midcentury style of visual representation is salient, given that a story like this one couldn’t, of course, have been filmed at the time. Until 1968, Hollywood studios observed the Motion Picture Production Code, commonly called the Hays Code, which prohibited nudity and “lecherous or licentious notice thereof” and “sex perversion or any inference to it.” By the 1960s, an informal liberalization of the Code would permit the representation of lesbian desire in, for instance, the belated film adaptation of Lillian Hellman’s 1934 play, The Children’s Hour. But that representation was conditional: lesbian desire had to be tragic, paid for through the loss of a life. In Carol, too, lesbian desire comes at a cost. Aird gives up custody of her daughter in exchange for occasional, likely supervised, visits. Still, Carol isn’t forced to pick either queer repression or fatal consummation. She can embrace lesbian love and a full life, and she does.

Whereas the cinematic representation of lesbian happiness proved impossible in the early 1950s, lesbian happiness itself, Haynes insists, didn’t. How does Haynes affirm the possibility of lesbian love and life at midcentury while maintaining fidelity to the aesthetics of an era that prohibited their representation? Part of the answer to this question lies in the medial displacement operated by Haynes and Lachman — the importation of an aesthetic of still photography into the domain of the moving image. With Carol, Haynes pastiches not ’50s cinema, as he does in Far from Heaven (2002), but ’50s photography. In its proximity to anthropology and sociology, the photographic style grants the alibi of documentation. Carol pushes cinema toward a journalistic art form that entails its own set of expectations regarding the representation of sexual difference. This representation, while subject to censorship, was never regulated by the Hays Code.

That in Carol photography saves cinema from homophobia is a simplistic observation, and a partial one. The happy ending is made possible not by cinema’s attunement to photography, but by the failure of both modes of representation. The ending depicts Therese and Carol’s first and second encounters after months of silence. At a restaurant, a nervous Carol invites Therese to move into her new apartment. Carol anticipates a rejection, and a rejection she receives. With nothing to lose, she professes her love. The declaration is neither reciprocated nor unreciprocated: a male friend hails Therese, thus interrupting the conversation. Therese heads to a party with the man in question, and Carol honors a dinner reservation with a group of friends. Soon, Therese leaves the party to return to Carol. The camera pans across the dining room, scanning for a familiar face. Having located Carol, Therese stands immobile for a few seconds before proceeding in her past-and-future lover’s direction. Slow motion prolongs each step. As Therese walks toward Carol, the frame jitters. Their eyes meet, and their mouths — Therese’s first, Carol’s second — curve into smiles, faint but exuberant. We cut to black.

The jittery frame constitutes an anomaly in a film where the camerawork otherwise emulates the titular character’s effortless grace. In the ultimate scene, the mode of representation that Haynes and Lachman have crafted out of cinema and photography appears too weak to bear the happy ending toward which Therese and Carol are headed. The frame trembles until it implodes, with a cut to black. Midcentury lesbian happiness can reside in cinematic form, after all. Or, more accurately, it can reside in a certain process of deformation: Therese and Carol gain access to a full life that is also a queer life through the dissolution of a mode of representation. If, for Leo Bersani, the formal glitches of Freud’s theory of sexuality dispense some truth about the incoherence of desire and relation, the dissolution of form in Carol predicates queer futurity on escaping a regime of compulsory visibility and legibility.

¤

Patricia White describes Carol as a reverie in her contribution to Reframing Todd Haynes: Feminism’s Indelible Mark, a new volume co-edited by Theresa L. Geller and Julia Leyda. A portion of Carol’s ending, stretching from Therese and Carol’s truncated reunion to Therese’s car ride to the party, reprises, from new vantage points, the film’s opening sequence. White receives the flashback that makes up the bulk of the film as lesbian wish fulfillment, a fort-da game wherein Therese gets to relive having Carol and losing her, knowing that she can now have her again. In White’s interpretation of Carol, too, a formal intervention — the framing device of the reverie — configures the relation between gender, sexuality, behavior, and identity.

The interplay between the formal and the social in Haynes’s filmography also piques Lynne Joyrich’s curiosity. Her essay for Reframing Todd Haynes submits that the filmmaker’s work “addresses cinematic and social issues, yoking the two together (and revealing how mediatized and social formations are always so yoked).” Joyrich has long formulated queerness in medium-specific terms; her 2001 essay “Epistemology of the Console” offered a televisual spin on a classic of queer theory, Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick’s Epistemology of the Closet (1990). For Joyrich, what sets Haynes apart is his commitment to problematizing both the intimacies and frictions between identity, on the one hand, and medium and form, on the other. The feminist and queer politics of Far from Heaven, Haynes’s homage to the melodramatist Douglas Sirk, emerge from the enmeshment of media history with the history of social and identity struggles. Far from Heaven, Joyrich summarizes, “thinks through its social questions by way of the media and mass cultural ones, revealing in the process how the two are always intertwined and how feminist and queer interventions thus necessitate media interventions, and vice versa.”

Reframing Todd Haynes sets out to assess the influence of feminism, primarily, on Haynes’s oeuvre. Wide-ranging in its themes, methods, and insights, Geller and Leyda’s collection dispels all doubts that a single-director focus might restrict scholarly ambition. Reframing Todd Haynes occupies a register of inquiry seldom rewarded by a contemporary academia that values garish polemics: a sustained, nearly obsessive, attention to individual films. The contributors’ patient interpretations make clear that the most meticulous methods for deriving meaning from art often are the most pleasurable to encounter.

Geller traces Haynes’s artistic and intellectual trajectories in a thoroughly researched introduction that draws abundantly on the filmmaker’s eloquent observations about art, theory, and identity. After the 43-minute Superstar: The Karen Carpenter Story (1987), featuring a cast of Barbie dolls, garnered copious praise from cinephiles but was prevented from circulating widely by copyright restrictions, Haynes made Poison (1991), his splashy debut feature. Caught in the controversies surrounding the National Endowment for the Arts in the late 1980s and early 1990s, the anthology film, a tribute to Jean Genet by way of Rainer Werner Fassbinder, has typically been associated with the loose movement that B. Ruby Rich has called New Queer Cinema (NQC). Geller reports that Haynes has struggled with the possibly reductive NQC affiliation, but has had “no qualms about being branded a director of women’s films.” Besides Far from Heaven and Carol, Safe (1995) and the HBO miniseries Mildred Pierce (2011) both concentrate on women’s status and experience. Fassbinder once observed that in Sirk’s films “women think,” and the same could be said of Haynes’s female characters.

Haynes truly earns his badge as a director of women’s films, in Geller’s estimation, through his continued engagement with feminist theories of form. Haynes is a scholar’s filmmaker if there ever was one. Undeniable is the impact of such film theorists as Laura Mulvey, Biddy Martin, Linda Williams, and Mary Ann Doane on his creative process. The privileged role that both female characters and feminist theorists occupy in Haynes’s filmography prompts Geller to inscribe it in a genealogy of “new feminist cinema,” where the filmmaker stands alongside figures like Chantal Akerman, who died in 2015 and to whom Reframing Todd Haynes is dedicated.

Some chapters in Reframing Todd Haynes carry the mission of situating Haynes’s work within a broader cartography of feminist cinema. Geller’s own mark on the volume’s first third proves indelible. In addition to composing the introduction, she co-authored one chapter and solo-authored another. The latter constitutes an impassioned rejoinder to Murray Pomerance’s critique of Haynes’s purportedly naïve gender and class politics in Safe. Pomerance, holds Geller, “would rather accuse Haynes of ignorant complicity than take the film’s ‘masculine-phobic’ critique of heteropatriarchy at face value.” Geller aligns Haynes’s stance on middle-class female domesticity in Safe with Akerman’s in Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975). Both films inhabit “sensitivity” as a site of feminist critique, magnifying the way “the slightest shift in pressure threatens to expose the extensive repressions and oppressions (desire, anger) required to maintain women’s compliance in heteropatriarchal capitalism.”

Bridget Kies, Mary R. Desjardins, and Rebecca M. Gordon all contribute predominantly feminist interpretations of Haynes’s films. Gordon, for example, addresses the filmmaker’s collaboration with actor Julianne Moore in Safe and Far from Heaven. (Moore also appeared in Haynes’s Wonderstruck [2017] and is set to star opposite Natalie Portman in his upcoming May December, currently in pre-production.) The chapter zooms in on the physical transformation undergone by Moore for both shoots. Moore was pregnant when she played Cathy Whitaker, a character who was not, in Far from Heaven. Efforts to conceal the star’s pregnancy, writes Gordon, “communicate unanticipated meaning.” In their uncanniness, Moore’s readjustments and realignments, somehow at once too sudden and too studied, mirror the film’s defamiliarization of the familiar as a pastiche of 1950s melodramas that were themselves, for the most part, adaptations and remakes.

Yet the ranking of Haynes’s credentials — as a maker of women’s films first, queer films second — proves wobblier than initially suggested. Many contributors turn their attention to the traffic between feminist and queer, terms that point to different, and, in each case, inconsistent, narratives of personal and collective identities, systematic critique, and social progress. At its best, Reframing Todd Haynes shows that the filmmaker’s corpus prevents us from defining one term without appealing to the other. In a superb chapter on, among other things, Haynes’s short Dottie Gets Spanked (1993), Noah A. Tsika picks as an epigraph one of the axioms inventoried in the introduction to Sedgwick’s Epistemology of the Closet: “The study of sexuality is not coextensive with the study of gender; correspondingly, antihomophobic inquiry is not coextensive with feminist inquiry. But we can’t know in advance how they will be different.” As he proceeds to “queer female stardom from MGM to Todd Haynes,” Tsika models an approach to Haynes’s work that doesn’t presume the stability of feminism’s meaning, queerness’s meaning, and the meaning that their collision produces.

The collection loses steam, if only slightly, when it labors to justify the privileging of feminism in both its subtitle and its introduction. Haynes’s track record as a good student of feminist theory can’t seem to dispel a certain discomfort around the decision to devote some 15 feminist essays to the work of a gay man. One strategy for managing this discomfort is to appeal, as do Geller (in the introduction) and Leyda (in a chapter), to a framework like Robyn Wiegman’s “queer feminist criticism.” This framework recognizes the interwoven political and theoretical genealogies that have shaped the rubrics of queerness and feminism.

Another strategy consists in registering the direct impact of women, and one lesbian in particular, on Haynes’s filmmaking, indeed on his very ability to make films. One chapter, by Geller and David E. Maynard, retraces producer Christine Vachon’s “filmic signature.” Vachon represents Haynes’s most important and consistent collaborator. A glance at her filmography — which includes such cult and critical favorites as Larry Clark’s Kids (1995), John Cameron Mitchell’s Hedwig and the Angry Inch (2001), Paul Schrader’s First Reformed (2017), and Janicza Bravo’s Zola (2020) — would suffice to convince anyone of her outsized impact on independent US cinema more broadly.

Acknowledging Vachon’s work and influence is essential, but in the context of Reframing Todd Haynes, the gesture has unintended effects. Anxieties concerning a clash between the volume’s politics and its subject’s identification are tethered to the current moment of identity politics. In the sexual taxonomies of the 21st century, categories that equate behavior and identity appear detached from histories that in fact, as Wiegman reminds us, overlap. Turning to Vachon for a solution to the problem of supposedly incommensurable politics and positions ratifies a contemporary configuration of identity politics that may not best serve feminist and queer interests. The gesture offloads onto someone else, a lesbian, the burden of staging a performance of the self that matches certain visions of feminism, queerness, and queer feminism.

If form is as important to Haynes as the volume’s editors and contributors assert — and it is — then we must take seriously the ways formal experimentation enables both the filmmaker and his audience to think of identity anew. In Haynes’s company, we may detach from the belief that identity categories constitute stable and transparent social facts that art merely reflects. In Carol, the deformation of a photographic style makes possible a midcentury lesbianism defined by its very invisibility and illegibility. Carol and Therese’s life together can begin only once they escape the film’s regime of representation.

An interest in illegibility also animates Haynes’s unconventional flirt with the biopic. Velvet Goldmine (1998) and I’m Not There (2007) allegorize the lives of musical icons who have embodied different archetypes of masculinity: the glam rockers David Bowie, Bryan Ferry, and Marc Bolan in one case, the singer-songwriter Bob Dylan in the other. Haynes plays with the notion of alter ego to distill something of these figures’ essence while estranging us from them. Haynes’s displacement of iconicity, Lee Edelman has held, exposes identification as self-differentiation — the management of an absence within the self. I’m not there.

¤

Haynes’s deviation from contemporary identity politics, paired with his predilection for period dramas, might suggest a romanticization of the past. His films, however, don’t return to some mythical “back then” when sexuality had yet to reticulate into the identity categories that now define us. The mediation of history grants opportunities for formal experimentation, and it is form, we have seen, that at least provisionally suspends the codes whereby identity is governed. Haynes has exhibited a fondness for the melodrama, a mode that, as he has noted and Jonathan Goldberg has paraphrased, risks inscribing “real women in a position of submission identical to their placement in the systems of domination feminism opposes.” In a number of Haynes’s films, characters find themselves crushed by the pressures of the identities they are ascribed and the positions they are made to occupy. At the same time, form, specifically what Haynes has called “homoaesthetics,”[1] cultivates a difference within the self to alleviate some of those pressures.

Haynes’s sharpest articulation of homoaesthetics may be Far from Heaven. It has often been said that the film makes explicit what in Sirk’s melodramas had to remain implicit. By this measure, the interracial friendship in Imitation of Life (1959) becomes, in Far from Heaven, an interracial romance between Moore’s Cathy and Dennis Haysbert’s Raymond Deagan. Likewise, the covert homosexuality of Rock Hudson, Jane Wyman’s co-star in All That Heaven Allows (1955), gives way in Far from Heaven to a character, Cathy’s husband Frank Whitaker (Dennis Quaid), who comes to terms with his own attraction to men.

But Haynes’s “appearing act,” if you will, is far from heroic. It casts doubt on the assumption that making the subtext text should clarify a film’s politics. After all, the interracial friendship between Annie Johnson (Juanita Moore) and Lora Meredith (Lana Turner) in Sirk’s Imitation of Life — or between Delilah Johnson (Louise Beavers) and Bea Pullman (Claudette Colbert) in John M. Stahl’s 1934 version — isn’t devoid of such romantic signifiers as faithfulness and shared domesticity. Far from Heaven’s homosexuality riffs on Imitation of Life’s homosociality, with new characters and settings. The inclusion of a gay male character in Far from Heaven, rather than signaling a self-congratulatory embrace of a liberal politics of visibility, brings into sharp relief queerness’s irreducibility to any one individual. Nothing in Far from Heaven is less queer than its prominent homosexual character.

Far from Heaven’s queerness lies, most of all, in its formal interventions. These activate processes of identification through which identity comes to appear different from itself — an imitation of life. The character best positioned to welcome queer identification in Far from Heaven is, improbably, not the legibly queer one, but the one whose life is troubled by queerness. The resentful and violent Frank invites little identification, which Quaid’s one-note portrayal only exacerbates. Spectators are encouraged instead to inhabit Cathy’s subjectivity, to see the world through her eyes. Cathy isn’t a queer character, but much like the glam rockers who inspired Haynes for Velvet Goldmine, a queer icon. She gasps, aches, regrets, and looks fabulous doing it all. Cathy longs to be free, similar to the scarf that a gust of wind sends flying off before Raymond recovers it. Sandy Powell’s impeccable costume design, in shades of violet, emerald, and rust, exemplifies what Sirk has described as the indistinction between “a dead thing and a live thing.” Moore’s performance is heightened and offbeat. She accumulates emotional “fakeouts,” looking as though she were about to miss the emotional mark, only for us to realize that we had the wrong mark in mind.

Queerness also lies in Far from Heaven’s own identification with Sirkian melodramas. Reframing Todd Haynes employs Elizabeth Freeman’s concept of “temporal drag” to designate, as Geller puts it, Haynes’s ability to convert “the pull of the past on the present in[to] affective and affecting scenarios.” With its parade of stylish outfits — no, looks — Far from Heaven underlines the drag in temporal drag. The film itself approximates a lip-sync performance to the tune of Sirk’s midcentury melodramas. The lip sync, here and elsewhere, induces difference in sameness. Rather than correcting the politics of the source material, it repeats them with a wink.

Perhaps best summed up by lip syncing, the “Haynes code” does not improve identity or history; it pastiches them and, in doing so, makes them inconsistent, unrecognizable, such that those who bear their weight might experience temporary relief.

¤

¤

Jean-Thomas Tremblay is the author of the forthcoming Breathing Aesthetics and a co-editor of Avant-Gardes in Crisis: Art and Politics in the Long 1970s.

¤

[1] In the out-of-print “Homoaesthetics and Querelle,” subjects/objects 3 (1985): 71–99.

LARB Contributor

Jean-Thomas Tremblay is the author of the forthcoming Breathing Aesthetics (Duke University Press, 2022) and, with Andrew Strombeck, a co-editor of Avant-Gardes in Crisis: Art and Politics in the Long 1970s (State University of New York Press, 2021). Their writing, scholarly and public, is tallied at jeanthomastremblay.me.

LARB Staff Recommendations

How Do You Solve a Problem Like “Titane”?

Is Julia Ducournau’s “Titane” feminist?

Betraying Camp

Alex Weintraub evaluates the Met's "Camp: Notes on Fashion," which has an "approach to fashion [that] is, ultimately, a self-defeating one."

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!

:quality(75)/https%3A%2F%2Fdev.lareviewofbooks.org%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2022%2F04%2Freframingtoddhaynes.jpeg)