BoJack the Centaur

By Evan Kindley

Dear Television,

We need to talk about BoJack. Now in its third season, the Netflix animated sitcom BoJack Horseman appears to be a bona fide hit (whatever that means, in Netflix terms). Certainly it’s got a dedicated following online and gets uniformly rave reviews, including from Pulitzer Prize-winning eminences. And yet so far we at Dear Television have not deigned to notice it, aside from a couple of favorable mentions in our 2014 questionnaire. This, friends, is unacceptable!

So, I’m going to get us started, Clifford Geertz-style, with some thick description. BoJack Horseman crossbreeds, for the first time in history, two species of television show: (a) the animated-series-for-adults, as inaugurated and defined by The Simpsons and currently exemplified by various offerings on Adult Swim, with its absurd universe, heavy joke density, and penchant for self-aware meta-humor; and (b) the existential-antihero-drama inaugurated and defined by The Sopranos and brought to perfection by Mad Men, with its depressive lead character, quasi-realist milieu, and recidivist long-arc plot structure, in which every season is basically the story of the protagonist either pulling themselves out of depression or sinking back into it. This format, it has been widely noted, is now cliché: audiences don’t seem to respond so readily to narcissistic misery any more, especially when it’s the narcissistic misery of a privileged white dude.

But even if the epoch of Difficult Men is finally over, there may still be some public sympathy left over for Difficult Stallions. BoJack repeats the beats of prestige tragedy as farce, this time with talking snow leopards. Over the course of fifty episodes, BoJack has gone on multiple benders, tried to sabotage his best friend’s wedding, made out with an old girlfriend’s teenage daughter, stalked his publicist, and [SPOILER ALERT FOR SEASON 3] contributed to the death by drug overdose of his co-star Sarah Lynn. Is this… supposed to be funny? Are we meant to find pathos or catharsis or tragic nobility in this despicable behavior, the way we were with that of Tony Soprano and Walter White and Don Draper? Does BoJack have cultural value as a portrait of toxic equininity?

But BoJack isn’t just a show about a jerk’s downward spiral: it’s also (like Mad Men and The Sopranos, come to think of it) a great example of a “hangout show.” In her 2003 New Yorker profile of Quentin Tarantino, Larissa McFarquhar defined the genre of “hangout movies” as

movies whose plot and camerawork you may admire but whose primary attraction is the characters. A hangout movie is one that you watch over and over again, just to spend time with them … [W]hen Tarantino … feels lonely he goes to a video store and rents Dazed and Confused, and then he doesn’t feel lonely anymore. The characters in the movie have become friends of his.

I submit that BoJack, whatever its other merits, very much works as a "hangout show." More so than on any other cartoon-for-grown-ups (and more on than most live-action sitcoms!), its characters are endlessly fun to spend time with. Not so much BoJack himself, who is kind of a horse’s ass, but the others — sober, sarcastic Diane Nguyen; spunky, loyal Princess Carolyn; asexual goofball Todd Chavez; sardonic Herb Kazzaz; daffy owl Wanda Pierce; and, most of all, that prince among Labradors Mr. Peanutbutter — these people (and animals) are quality hangs. And we get to know them intimately, in the same way we did the casts of Friends and Seinfeld. For an animated series in which literally anything can happen without requiring anyone to scout locations or build new sets, an enormous chunk of the show takes place in Bojack's apartment, Princess Carolyn’s office, and a handful of other locations, and there's a surprising amount of downtime between narrative incidents. Again, I feel like this is a big departure from the pattern set by The Simpsons and followed by most of its epigones, in which action tends to be much more antic and constant. (The Simpsons began life as an animated family sitcom, but these days it’s closer to a surrealist picaresque.) With BoJack, as in the show-within-a-show Horsin’ Around, much of the fun to be had is not in the zany weirdness but in the simplest of sitcom pleasures: hanging out, shooting the breeze, horsing around.

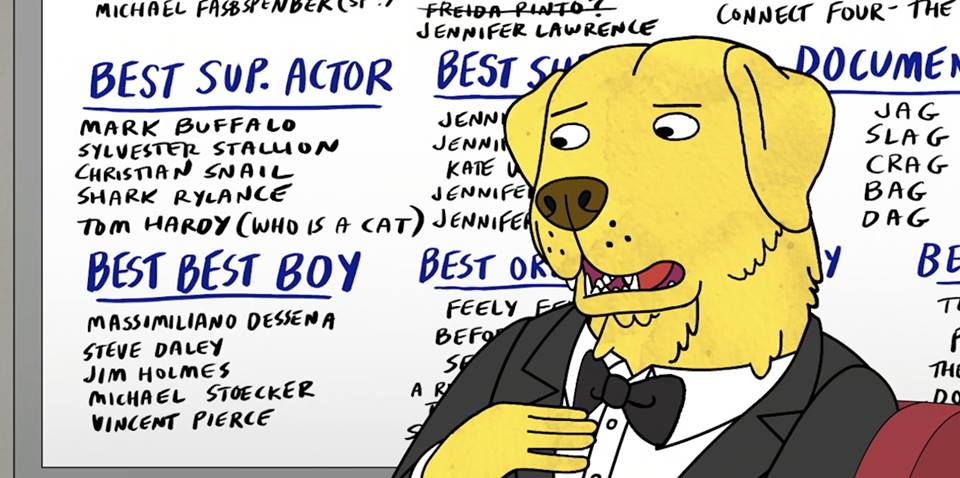

But of course there is plenty of zany weirdness, too, which brings me to a final observation: BoJack Horseman provides a master-class in verbal comedy, and in particular the comedy of puns. I got started thinking about this aspect thanks to this Vulture interview with creator Raphael Bob-Waksberg, who winningly describes punning as “math and … sex and … comedy all in one.” Puns are a big part of lots of TV comedies (The Simpsons again, Arrested Development, Community, 30 Rock), but the level and degree of wordplay in BoJack is unprecedented. BoJack’s agent Marv has a poster on his wall for the movie His Squirrel Friday; books on Princess Carolyn’s bookshelves include Purrsepolis, Purrity, Me Meow Pretty One Day (especially cute when you realize that the sister of its author voices Carolyn), The Color Purrple, and, the pièce de resistance, Purrmese Days; and just look at the lists of Best Supporting Actor candidates on this whiteboard:

The oft-repeated cliché about puns is that they are “the lowest form of wit” (actually this is a distortion of a quotation, sometimes attributed to Oscar Wilde, about sarcasm). But, low or not, BoJack uses puns as the building blocks for exquisite creations. Puns are to BoJack Horseman what made-up medieval history is to Game of Thrones.

Puns are inherently writerly, of course: these little fillips of verbal cleverness remind us that there are people constructing this artificial world for our benefit, and fussing with every little detail to get it just so. The great literary punmakers (Joyce, Nabokov, Perec) have also been control freaks. It’s this, I suspect, that bothers some people about wordplay, as much as the supposedly “easy” or “automatic” nature of it: it’s anti-absorptive. Not everybody wants this kind of Verfremdungseffekt mixed in with their cartoons.

One last thing before I hand the keys over to Jane. BoJack’s whole-hog embrace of punning seems somehow related to the other main current of "dumb humor" in the show: the constant gags involving animals and animal behavior. I’m thinking about Princess Carolyn being excited about receiving a box with tissue paper inside, for example, or Mr. Peanutbutter’s favorite TV show being Bones, or — my personal favorite — the drinking bird BoJack and Sarah Lynn encounter at an Alcoholics Anonymous meeting (“I was stuck in a terrifying cycle of drinking, lifting my head up, drinking, lifting my head up”). The show pushes these sorts of “dumb” animal jokes so far, sometimes, that they start to seem almost sophisticated, even avant-garde. And, of course, this kind of thing helps offset the bleak psychological realism of the show's basic plot. (Bob-Waksberg: “Sometimes we worry, ‘Are we going too dark with this scene?’ ‘Is this gonna be too much of a bummer?’ And then we remember, ‘Okay, it’s a horse talking to a spider. Just remember that part of it.’”)

There! We’re out of the gate, and now I want to hear what Jane and Phil think.

That’s too much, man,

Evan

¤

Bad Seriality and the Horseman Universe

By Jane Hu

Dear Television,

Earlier this month, I went to Dickens Universe — a weeklong conference among the UC Santa Cruz campus redwoods that focuses, each year, on a different Dickens novel. What does Dickens have to do with television, you might ask. Well, not much, some have argued. But there was one talk during my week with Dickens that struck me as more than a little r-e-l-e-v-a-n-t to what I’ve been thinking about in terms of shows like BoJack Horseman.

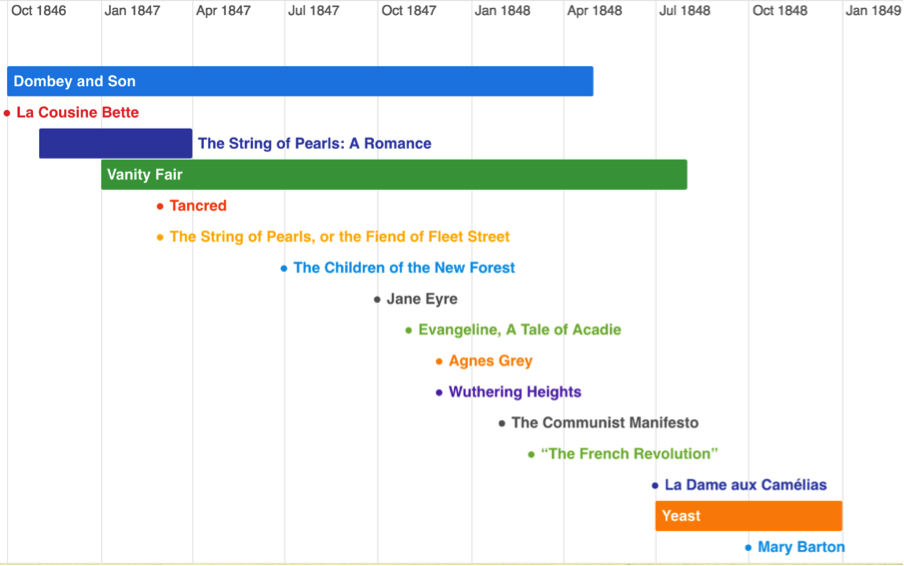

Robyn Warhol, a specialist of 19th-century seriality, gave the closing lecture on her project of collating sections of Victorian novels in the order they were originally published. Like a lot of Victorian novels, it’s online and it’s compelling on even just a glancing level. If you squint hard enough, it looks like Wuthering Heights is giving birth to The Communist Manifesto!!!

Warhol’s talk reminded me that perhaps the closest thing we have to Reading Like A Victorian — that is, simultaneously following multiple separate plots as they unfurl over a period of time — is Watching TV Today. Except, of course, when it comes to binging.

When Evan wrote his above post, it was shortly after the July 22 release of the entire third season of Bojack on Netflix. Anticipating my own response, I also began to watch all of season three during a Sunday afternoon that, very quickly, bled into Sunday evening. Somehow, I had convinced myself that powering through a 12-episode season at around 26 minutes an episode would take a few hours tops. Instead it took over five hours and — more importantly — felt somewhere closer to ten.

I really like BoJack Horseman, but binging season three — its most disjointed and experimental to date — was nauseating. The experience of propelling myself through all its narrative hurdles and relays felt like an endurance test and, ultimately, so grueling that it has taken me whole weeks to confront it again. Hey.

In her talk, Warhol emphasized that seriality is defined not just by the distribution of a narrative into parts, but by the added structural reality that there are actual temporal gaps between each part. The experience of not watching — of waiting — between each serial part cannot be discounted. Reading a Victorian novel today at one’s own pace, or binging a television series sans breaks, is not to read like a Victorian, or to watch TV like a, I don’t know, Baby Boomer?

BoJack creator Raphael Bob-Waksberg is more than aware of what I’m going to call the recent lack of seriality — or maybe the Bad Seriality? — of television today:

[Y]ou couldn’t do this 10 years ago. Even now on network and cable they’re more serialized than they used to be, but they still have to have some amount of enter-ability for every episode. Netflix shows don't have to do that at all if they don’t want to.

But what if, for a show like BoJack, the loss of seriality doesn’t just alter, but actually frustrates our engagement with it? Especially because BoJack is so formally interesting, it seems possible that one is not meant to consume it as an undistinguished whole.

*** “Like three of the first four episodes is a bottle episode! This show is nuts!” – personal email from Phil Maciak, 24 July 2016 at 16:01 ***

What do I remember from my fugue-state, fever-haze first viewing of season three? Off the top of my head: silent underwater episode, Sextina Aquafina abortion bait-and-switch episode, Princess Carolyn’s new and relatively deadpan human assistant, a literal hamster house, bottles, the image of a bottle, the bottle as metaphor, wine bottles, beer bottles, a car crash, blackouts, a narrative car crash in the final few episodes as BoJack drives his life into the ground once again. The general arc of season three is actually reminiscent of prior seasons insofar as BoJack’s life always takes a downward spiral toward the end. And perhaps it’s the cumulative echoes of these repeated mistakes that make it increasingly dizzying when following BoJack to what are now his predictably bad endings.

But while repeated themes and sight-gags echo over the course of the new season, I’m not quite sure how it all fits together. Themes and images repeat almost poetically in BoJack, but do they develop in quite the same way as they would in a cumulative narrative? And maybe it doesn’t need to! Maybe that’s the point… ah ha, I’ve c-r-a-c-k-e-d it.

Evan described BoJack as a “hangout show” — one where viewers can dip in and out at their own leisure not so much because of any constant narrative propulsion, but simply because we like spending time with its characters. Perhaps this way of looking at BoJack — as separate bottle episodes that share reliable characters and narrative tropes — helps us imagine how it works as a hangout show. But what happens, as the season three finale suggests, when the horse you’re hanging out with only ever confirms that he will never stop acting like a dick?

As show creator Raphael Bob-Waksberg has described:

We like to have a little bit of episodic-ness to our show and make every episode feel like it has a beginning, middle, and an end of itself. It's not just a Boardwalk Empire style chapter in a longer saga.

The “episodic-ness” of BoJack — in which each episode contains a story arc in and of itself — fits the form of all of BoJack’s own coke episodes and booze binges. I kid you not that binging all of season three of BoJack is sort of what I’d imagine a drug trip is like. In a way, the show’s narrative models this: nadirs of BoJack’s self-destructive cycle don’t really carry forward into the larger saga of his life, but are only recycled as repeated instances of narrative amnesia. Except Bojack keeps blacking out, and we as viewers don’t.

While Bob-Waksberg welcomes and indeed expects viewers to binge on BoJack, he also banks on the promise that we will interpret it “in order,” or, serially:

I’ve said before that one of the great discoveries in season one was this realization that the audience is going to watch the show in order, and we can really use that to our advantage. Even the idea that they're going to watch it quickly and they're going to binge watch it on schedule and in order is a tremendous thing as a storyteller to bet on.

While BoJack might be at times narratively schizophrenic, it nonetheless charges forward in a linear model. Which is what makes its manic bottle-episode/flashback/hallucinatory structuring both so difficult and painful to watch. Pace yourself, is what I’m suggesting.

An experiment that would be interesting to conduct is to set up a schedule where one watches Netflix-released shows in incrementally pieced out installments. What would Bojack look like reengineered and redistributed like your favorite show from back in the nineties?

I'm not saying you look bad; just much, much, much older,

Jane

¤

BoJack Horsewave

By Phil Maciak

Dear Television,

I just read a thing today about a new meme called Simpsonwave. I’ll let writer Kevin Lozano describe it:

Basically, Simpsonwave constitutes a genre of YouTube videos that collage classic Simpsons moments with vaporwave tracks. The clips from The Simpsons are often heavily edited, given a codeine purple filter, a static-y VHS feel, and generally arranged with psychedelia in mind. Overlaid on these clips are the classic vaporwave sounds of John Carpenter synths, cheesy muzak saxophones, and skittering drum machines, making the otherwise strange edits feel complete. The mashup of the both is startlingly relaxing. Those early seasons of The Simpsons are reeking with 90s nostalgia and flashes of surrealism, while vaporwave accesses something deeper in that energy, tapping into a sort of dreamy ennui.

This isn’t wrong. Simpsonwave is super-relaxing once you get over the suspicion that you’re actually watching a dark-web occult murder video, and Lisa is going to crawl out of your laptop and literally scare you to death like the girl in The Ring. It’s a nonsense collection of signifiers — vaporwave, VHS aesthetics, The Simpsons — but, like a good cocktail, or a good Netflix show, it hits the spot. And both Evan and Jane’s posts are making me think of it in relation to BoJack.

For one, I think there’s a kinship to what Evan’s calling the “cross-breed” between The Simpsons and The Sopranos. Every show is influenced by something, so much so that a series like Stranger Things or Mr. Robot can be accused of having no there there beneath all of its allusions. These homage-style series are palimpsests of a very curated set of inspirations/echoes/hyperlinks. But even as they grasp after nostalgia or hipster credibility, I want to say that there’s a kind of subtlety to the enterprise. They want you to see what they’re doing, but they want it to also to be able to disappear. Even as Fight Club might be the actual first thing you think of when you see Mr. Robot, I’m sure that Sam Esmail — Kubrick posters on all the walls of his dorm room — wants the reference to be available only if you look hard enough. Similarly I suspect the Duffer Brothers want there to be maybe a brief delay before viewers realize that this show feels so lived-in because they actually did live in it in the early eighties. It’s not that subtle — Stranger Things, almost like Fargo (the TV series) essentially markets its indebtedness — but it’s aspiring to an elegance in its allusive framework that doesn’t pound the viewer over the head. Or, at the very least, they want you to feel like there’s more in The Upside Down than references to other movies.

BoJack, like Simpsonwave, is not particularly subtle about its influence. This one unlikely thing plus this other unlikely thing makes this third unlikely thing. Part of the show’s premise, its foundational shock, is the strangeness of an anti-heroic talking animal, a phallic narcissist with hooves, a horse with a long face and a long face. The sight-gag punning of animal-people that populates the show is a kind of mirror for the way the show itself is a brute-force, Dr. Moreau amalgamation. So it makes sense that the show loves literalizing puns as much as it does. Bojack Horseman is a science experiment of exactly the kind that Evan identifies. It doesn’t want you to hunt around and find its influences, be delighted around each turn when it subverts or meets your expectation, feel a pang of longing or superiority when you recognize a shot framing. It wants you to see them immediately and then forget them. If the great dare of the Sopranos era of anti-heroism is to make viewers feel empathy for monsters, the dare of BoJack is to make you cry about a horse betraying a human woman.

But, to Jane’s point about the show’s “bad seriality,” I think there’s another resonance between BoJack and Simpsonwave. Jane, you quote Bob-Waksberg talking about both the way that BoJack embraces the ability to do somewhat contained episodes and the way that it takes advantage of the viewer’s “interpretation” of those episodes in order. It’s a funny way to think about seriality, and maybe it’s a little aw-shucks disingenuous. I mean, beyond the fact that this is just how seriality works in general, this show plants reveals very very early, and it builds on serialized jokes — the spaghetti strainers — better than any show since Arrested Development. But this characterization is right inasmuch as BoJack seems less invested in using seriality for plot than for affect. It doesn’t want to utilize the serial management of narrative threads in order to bring us to the end of a particular story so much as it wants to use those threads to make us feel sick or perversely hopeful or — in the manner of a hang-out show — comfortable with our friends.

In a terrific interview with the Nerdist Writers’ Panel podcast — and a bunch of other places as well at the time — Raphael Bob-Waksberg and Lisa Hanawalt talked about the decision to trick the audience in the first season into thinking the show was much lighter than it was. In other words, the idea was to invite the viewer into a cartoon with the same kind of alt-comedy vibe as Bob’s Burgers or Archer, only to slowly — serially! — reveal that what they’re really watching is a difficult men-era tragicomedy. The premise of the anti-heroic horse is there from the beginning, but it takes a couple of episodes before genuinely bad stuff starts to occur, before things go dark. There are lots of interesting reasons to pitch-shift in this manner, but one big one — the biggest, to me — is that the prevailing takeaway for that season is the feeling of growing dread. What happens in the first season of BoJack Horseman? I can’t quite remember the plot points, but I do remember that things started out okay and then got sadder and more hopeless before a brief vision of light at the end. What Jane’s calling bad seriality is maybe less about the “serial” than it is about the “bad.” Simpsonwave is non-narrative, it’s about the creation and sustenance of a very particular vibe. BoJack isn’t non-narrative, and I don’t want to suggest that it’s in any way uninterested in plot, but, in every season of this show so far, the clearest skill Bob-Waksberg has demonstrated is his ability to use a season of television to both set and kill a mood.

Maybe that’s what seriality is in broad strokes. Maybe Dickens was just trying to ruin everyone’s day by messing with all those poor orphans. Maybe serial storytelling, binged or otherwise, is just mood management. But even if that’s true, there’s something refreshing about the extent to which Bojack openly embraces that charge. Whether it’s exasperation or sickness or amazement, it’s the feeling that counts. It’s a show about a horse who doesn’t feel anything, but it makes us feel everything. Then it’s over, and we pack up and leave the Dickens Universe.

Botticelli, Barbarelli, Beetle Bailey,

Phil.

LARB Contributors

Phillip Maciak (@pjmaciak) is the TV editor of the Los Angeles Review of Books. His essays have appeared in Slate, The New Republic, and other venues, and he's co-founder of the Dear Television column. He's the author of The Disappearing Christ: Secularism in the Silent Era (Columbia University Press, 2019) and Avidly Reads Screen Time (New York University Press, 2023). He teaches at Washington University in St. Louis.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Game of Thrones: Season 6, "The Winds of Winter"

Winter is here!

Game of Thrones: Season 6, "Battle of the Bastards"

Evil Father’s Day: or, We’re Not Going to Do That, at Least Maybe Not

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!

:quality(75)/https%3A%2F%2Fdev.lareviewofbooks.org%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2016%2F08%2Fmaxresdefault.jpg)