AFTER COLLEGE, I worked for a couple years on ranches in the Southwest. My duties consisted of standard cowboy things: mending fence, moving pastures, branding, doctoring, and the like. During this time, I never heard another hand recite poetry. Most days, we hardly talked at all. I knew of the Gathering at Elko — the rich culture of cowboy poetry and song, the renowned community — but my only exposure to the genre was an old paperback I skimmed in the bookmobile outside the tiny town of Newkirk, New Mexico. It was basic fare: rhymed iambic couplets, stories of troublesome mares or bunkhouse antics. I saw a predictable language and familiar plot that had been as much influenced by Hollywood as Hollywood had by it. The Myth had won, I supposed. The image on the screen had stepped out, saddled up, and begun speaking in verse.

This is what many might imagine when they learn of cowboy poetry. After 30 minutes in the Elko Convention Center, among the bobbing hats and displays of chaps, turquoise pendants and tall, tooled boots, it would be easy to think the same. In my few days at Elko, I visited J. M. Capriola, best tack shop in the Great Basin, home to the famous Garcia bits and spurs; I watched musicians jam in the restaurants around town, playing tunes I knew from ranches; and I swigged fiery Picon Punch at the Star Hotel, Elko’s night-life hub and long-time Basque establishment.

All this to say, the 35th National Cowboy Poetry Gathering provided the spectacle and excitement one expects — shiny tack and old-time charm. But beneath these pulpy trappings, one also finds a subset of cowboy poetry distinguished by its lyricism and attention to its content — family, nature, labor, history. One finds a poetics rooted in public speech, subversive of ranching and rural stereotypes, which subtly navigates nostalgia to express an authentic vision of belonging.

II. Myth or Reality

The first cowboy poems trace their origins to the post–Civil War trail drives, when massive herds were pushed north across the plains from Texas. These crews of men on horseback drew from a variety of traditions to craft their verse, sitting around a fire or entertaining between periods of work. Early poems mixed the ballads of sailors and soldiers from the British Isles, the songs and rhythms brought by black cowboys from the South, the corrido tales of old vaqueros, and popular Victorian poetry of the day. Browning and Tennyson lent their expertise; Longfellow followed suit.

Over time, the isolation and open space of ranches provided ground for the genre to flourish. The “golden age” of cowboy poetry occurred between the turn of the century and World War II, when poems began to appear in print and the open range was becoming fenced. But as the century progressed, the practice of recitation waned, due to development, mechanization, and increasing rural emigration. Worried about preserving this aspect of cowboy heritage, a cohort of folklorists from across the West (led by this year’s keynote speaker, Hal Cannon) planned the inaugural gathering at Elko in 1985. They chose the end of January, when work on ranches slows. A few hundred people attended the event, and it was such a success that another was planned for the following year.

The Gathering is now a weeklong celebration that draws 5,000 people annually. Inside the convention center, I watched tourists and locals, singers and storytellers, city- and country-dwellers all mill together. Most were male ranch folk on the far side of 50, shouting greetings like old college roommates. The attendees drank coffee and browsed art at the silent auction, then queued for favorite shows. Outside, the morning was warm for the season, a mere 40 degrees, the surrounding mountains melting snow.

“When we first got started, we didn’t know what it was gonna be like,” Waddie Mitchell told me. A lifelong Buckaroo from Nevada, Mitchell also helped to organize the first gathering. “Cowboy poetry, that sounds like such an oxymoron, because you didn’t see John Wayne in the movies sitting around spewing poetic.” He partly attributes the Gathering’s popularity to this notion — outsiders perceive the concept so surreal as to be entertaining. “But it became a family and it just got better every year,” he said. “When you get an artist community together, that raises the whole art form.”

Moments before our conversation, I watched Mitchell stand on the stage of the Ruby Mountain Ballroom. He planted his boots, denim jacket buttoned tight, and stared out beneath the brim of his hat. He tucked his thumbs into the pockets of his jeans. He leaned, grinned, stroked his waxed mustache, and launched into a poem which, two stanzas later, he entirely forgot. His wife ribbed him from the audience. No one else seemed to mind. Mitchell chortled and apologized before beginning another, a fan favorite, about a man on the edge of a cliff, admiring the view, unseated by a gust of wind, falling to his death and imploring God to save him:

“God, if you help me now I’ll quit my sinful ways.

I’d do the things you’d have me do and I’ll work hard all my days!

I’ll spend time with my children; I’ll help my lovin’ wife.

I’ll quit the booze and whiskey and I’ll turn around my life.

I’ll work to help the needy and I’ll promise to repent…”

Just then a tree limb caught his coat and stopped his fast descent.

And while hanging from that tree that grew out of that rocky shelf,

He looked skyward saying, “Never mind! I handled it myself!”

The poem is typical of many at Elko: entertaining, heavily performed, standard in rhyme with less than perfect meter. When the clapping and chuckling ceased, Sid Marty, a longtime park ranger from Alberta, Canada, rose and began an ode to barbed wire. He wore glasses, a bright orange scarf around his neck, and a knife at the hip. I had to strain to hear his words:

… feeling religious

I forgot the mountain slowly rising

underneath this sod …

[…]

The season winds out endless snares

we are as much closed out as in …

This is also exemplary of many poems at the Gathering: reflective, humble, more concerned with limits than with riding open country or roping calves.

Amy Hale Auker, who has attended the Gathering since 2002, discussed the challenges in writing of a life co-opted by pop culture. “It is a very hard barrier to break,” she said. “I write some serious poetry […] but we have this clown image, the Hollywood image,” which distracts from the reality of the work.

In “Letter to my Father,” Auker shows what it means to undermine those tropes:

The first time I saw you cry,

I was four.

A heifer stood beneath the windmill,

Dripping blood.

A pack of town dogs

Had chewed her face off.

It was also the first time

I saw you load a gun.

Gone is the cartoon cowboy image, replaced by a heartfelt and traumatic family moment. The realities of ranch work intrude on the tough, pistol-wheeling stereotypes. Today, Auker works as a cowboy for the Spider Ranch in Yavapai County, Arizona. “I think on-the-ground experience will keep us from writing in clichés,” she said. “My fresh voice will come from intimacy with my piece of country, 50,000 acres in the Santa Maria Mountains.” Auker also emphasized the importance of being a woman, one of the relative few who perform at the Gathering: “I’m already outside of the cliché,” she said. “I’ve been outside of the cliché for a lot of my life.”

III. A Record and a Ritual

One afternoon, I watched Auker recite her poetry on stage, joined by Deanna McCall and Olivia Romo, both from New Mexico, a rancher and farmer respectively. McCall performed her poetry in a low drawl, a black hat atop her head. Her poems recalled the travails of working cattle in rough country, the particularities of tack, and the best tactics for negotiating brush. She then read a poem about feeding “cake,” a pellet-shaped supplement that can be used to woo unruly cattle. Romo followed with slam-inspired poetry about the acequia culture of her native Taos.

The subjects of these poems, and the entrance of women onto the cowboy poetry scene, are examples of the way cowboy poetry serves as a record for the shifting West. The genre has expanded since its creation; it recounts folly and describes outlandish characters, yes, but it also documents movement and settlement on the arid range, and has become somewhat more inclusive. Buck Ramsey’s poetry, for instance, laments the varied “progress” of civilization. Wally McRae skewers the practices of strip mining. Elizabeth Ebert writes humorous, beautiful portraits of daily life. Henry Real Bird blurs the differences between cowboys and Indians. Andy Wilkinson examines the history of water consumption. Yvonne Hollenbeck attends to the natural seasons, then easily assesses popular culture.

These writers show how cowboy poetry — like any folk storytelling — creates a specific understanding of a place and its challenges. The same can be said of Australian Bush Poetry, or the poetic traditions of gauchos from South America, or of loggers from the Pacific woodlands. More recently, as Craig Miller argues in his essay “Nature and Cowboy Poetry,” many cowboy poets “are registering a powerful alarm at the rapidly increasing pace of urbanization and environmental degradation [in the West].”

Which is why nobody I spoke with at Elko much cared that cowboy poetry, on the whole, receives such little attention from the literary establishment. It’s not about writing what others deem elite. Nearly all the verse is written to be recalled and shared, and this sharing brings a community together; it bridges the great spaces between ranches and alleviates the isolation inherent to cowboying. “We need to make sure this event remains a gathering rather than just another festival,” said Auker, quoted during Cannon’s keynote. “We gather because we have a common story, told in unique voices, in a variety of forms. We gather to share stories.”

And they gather, I’ll add, to fulfill a ritual. The event at Elko is only the most prominent of a number of gatherings across the country. Chris Henrich, a cowboy poet from Solvang, California, has attended for 10 years. “[I’m] kind of like a priest going to the Vatican,” he told me. “I come here to be inspired and go back and preach cowboy poetry to my little gathering at the Alisal Guest Ranch.” The poetry can strike outsiders as repetitive or drab — silver spurs, again; dusty boots, again — but even this emphasis on gear is a means to affirm a shared culture. For a poetics rooted in nomadic labor, it’s no surprise that Elko has developed such a congregation.

IV. Where Wisdom Resides

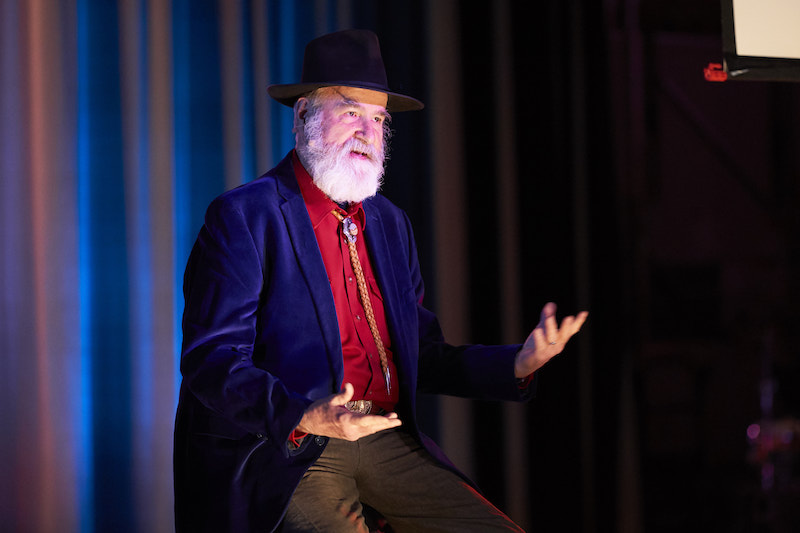

My first morning, I hustled into the main auditorium to watch Hal Cannon’s address. The curtains parted, and the Elko High School marching band performed. The students wore plumed hats, red uniforms, white shoes that shone as brightly as the brass. Cannon appeared onstage a moment afterward. He held a banjo and moved to a stool in a circle of light. He greeted the audience briefly before closing his eyes and beginning to play, a lively string-band tune.

His speech, titled “Where Does Wisdom Reside?,” surrounded the question but avoided confronting it head-on. In classic folklorist fashion, Cannon quoted his peers at length, mining previous keynotes and the archives of cowboy verse. His answer, it seemed, was that wisdom resides in a collective past.

“Will these poems, these stories, this wisdom speak to the generations coming up?” he asked. The address bore a distinct tinge of nostalgia, the fear that cowboy poetry and cowboy culture are under threat. Of course, this is a frequent theme at the Gathering. Cowboys have always worried that their life would disappear: first from the Homestead Act, in the 19th century; then by barbed wire, the end of the trail drive; later by tourism, the dude ranch, development, industry, and misguided environmentalists.

In response, Cannon played a clip of Buck Ramsey’s classic poem “Anthem,” the prologue to his 50-page epic, “As I Rode Out on the Morning”:

It was the old ones with me riding

Out through the fog fall of dawn,

And they would press me to deciding

If we were right or we were wrong.

For time came we were punching cattle

For men who knew not spur nor saddle,

Who came with locusts in their purse

To scatter loose upon the earth.

On the surface, Ramsey’s poem might support Cannon’s notion of wisdom held in common. He offers wise words on the history of ranching, but those words prove critical as well — not only of wealthy landowners, but of his fellow cowboys, partners in that common past, who were complicit in overgrazing the range. Such conflicts also exist in the common present: in contrary beliefs regarding climate change or sustainable management.

Other poets, like John Dofflemyer, a rancher in the Sierra Nevada foothills, are equally critical of their contemporaries, further complicating the idea of a common wisdom. Today, Dofflemyer is something of a renegade at Elko; he’s not sure his poetry even falls within the genre: “After 31 years, I’ve kind of strayed off the hackneyed, the same old cowboy shit, and tried to integrate what’s happening in the here and now,” he told me.

Throughout the early 1990s, he published Dry Crik Review to offer a platform for more voices and styles. At the time, many cowboy poets scoffed at open verse. “There was one issue that was damn near all women,” said Dofflemyer. “Christ, the men went nutso — I mean, this culture is pretty male, especially in 1990 […] but the bottom line was, women were writing stronger stuff than the men. The men were over here with all this bravado, and the women were writing poetry about their alcoholic husbands.”

If there’s wisdom to be found, it lies in attending to these disagreements — about subject, about style, about the best way to rope or when to rotate cattle through one’s pastures. The differing opinions of the participants at Elko attest to its vibrancy as much as the hats or displays of chaps.

In the words of Wallace Stegner, “The Westerner is less a person than a continuing adaptation. The West is less a place than a process.” While at the Gathering, I often considered the cowboy in terms of this adaptation, and the range in terms of this process. It’s true that the ground beneath the cowboy has changed: the number of ranches is in decline, and technology has enabled family units to do more, lessening the need for single, itinerant laborers. But despite these shifts, and despite the cowboy’s mobile and checkered past, certain elements endure: in their storytelling if not their stories, in techniques to handle stock on varied range.

That summer out of college, as a hand in New Mexico, I learned to work cattle in the rodear method of early vaqueros; we formed a corral of riders in the corner of a distant pasture and sorted the herd without the stress of pushing them all back to headquarters. It’s work like this — traditional, attuned to regional needs — that many cowboy poets pride as the wellspring for their writing, and through which another type of wisdom emerges.

“That’s the depth of which the place owns you,” Dofflemyer told me. “You don’t own the place. I might own several thousand acres of a cattle ranch, but that son of a bitch owns me. It tells me what to do. It dictates when I have to pump water. It dictates when I have to move the cows. And it’s my comforter.” This is how he belongs. At Elko, one feels most cowboys, most poets, would say the same: “When I’m here, the ranch comes with me.”

¤

Sean McCoy is a writer from Arizona. He edits Contra Viento, a journal for art and literature from rangelands.

¤

Banner image: Chilton Centennial Tower in Elko, Nevada, site of the National Cowboy Poetry Gathering.

Photos in this article by Marla Aufmuth, ©MARLA AUFMUTH, marlaaufmuth.com.

LARB Contributor

LARB Staff Recommendations

Reverse Cowboy

Disentangling fact from myth in the figure of the American cowboy.

A New Voice of the Southwest

When the going gets weird in Southern New Mexico.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!

:quality(75)/https%3A%2F%2Fdev.lareviewofbooks.org%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2019%2F03%2FMcCoyCowboy-1.png)